Building an AI Ops Agent: Durability with Inngest AgentKit & Otel

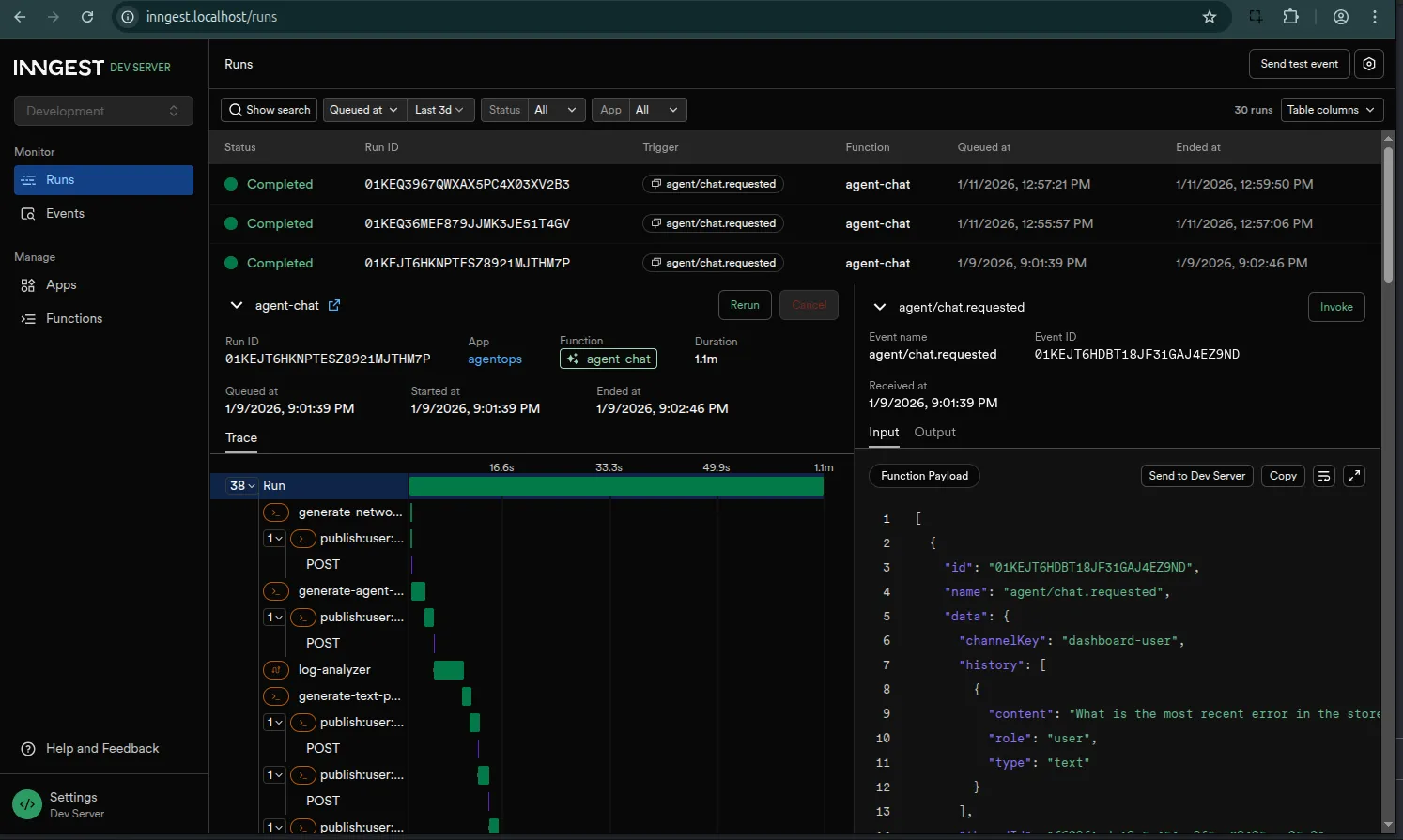

The Inngest Server Development dashboard

The full source code for the project discussed in this article is available on GitHub.

In Part 1, I set out to build an autonomous AI Ops agent—a digital teammate that could actually diagnose and fix distributed systems, not just chat about them.

By Part 2, I had hacked together a custom event-driven architecture to keep it running. I called it a “durable loop.” And honestly? It worked. But it also revealed a painful truth about building agents: the plumbing is heavy.

I found myself writing more code to handle state persistence, retries, and race conditions than I was writing for the actual agent logic. I was accidentally building a distributed systems framework instead of an ops tool.

So today, I’m refactoring. I’m deleting my custom loop and moving to the Inngest AgentKit. This gives me a framework that handles the hard parts of durable execution and provides deep observability via OpenTelemetry, allowing me to see what’s happening inside the black box.

This acts as a formalization of the event driven architecture established in Part 2. Because Inngest is inherently event-driven, it carries over many of the same principles we discussed previously—just without the heavy lifting of maintaining a custom event bus.

Why a Framework?

In the first two parts of this series, I learned that building a reliable agent system isn’t really about the LLM calls. We tend to fixate on the prompts, but the real challenge is what happens between them.

I found myself constantly battling the “What Ifs” of production:

- Durability: What if the server crashes while the agent is “thinking”? Does it wake up with amnesia, or does it pick up exactly where it left off?

- State: How do I persist the conversation history and tool outputs without writing a custom database adapter for every single turn?

- Human-in-the-Loop (HITL): How do I pause execution for human approval without holding an HTTP connection open for 4 hours and timing out the load balancer?

I realized I was spending 80% of my time building a distributed systems framework and only 20% on the actual agent behavior.

There are other great tools emerging in this space. LangChain (and LangGraph) is the massive incumbent with a huge ecosystem, though I often find its abstractions can obscure the underlying logic. Microsoft’s AutoGen is fantastic for multi-agent conversations but feels primarily Python-centric.

I chose the Inngest AgentKit because it solved the specific “plumbing” problems I hit in Part 2:

- Infrastructure-Level Durability: Unlike library-level solutions that run in memory, Inngest manages state at the infrastructure level. It handles retries, persistence, and long-running sleeps automatically.

- Native TypeScript: It fits perfectly into my existing Hono/Node stack without forcing me to context-switch languages.

- Developer Experience: The local dashboard is a game-changer. Being able to inspect an agent’s run, replay events, and debug step-by-step saves hours of console.log debugging.

- OpenTelemetry Support: It integrates deeply with OTel out of the box, which is critical because—as I learned the hard way—you can’t fix an agent you can’t see.

The Architecture

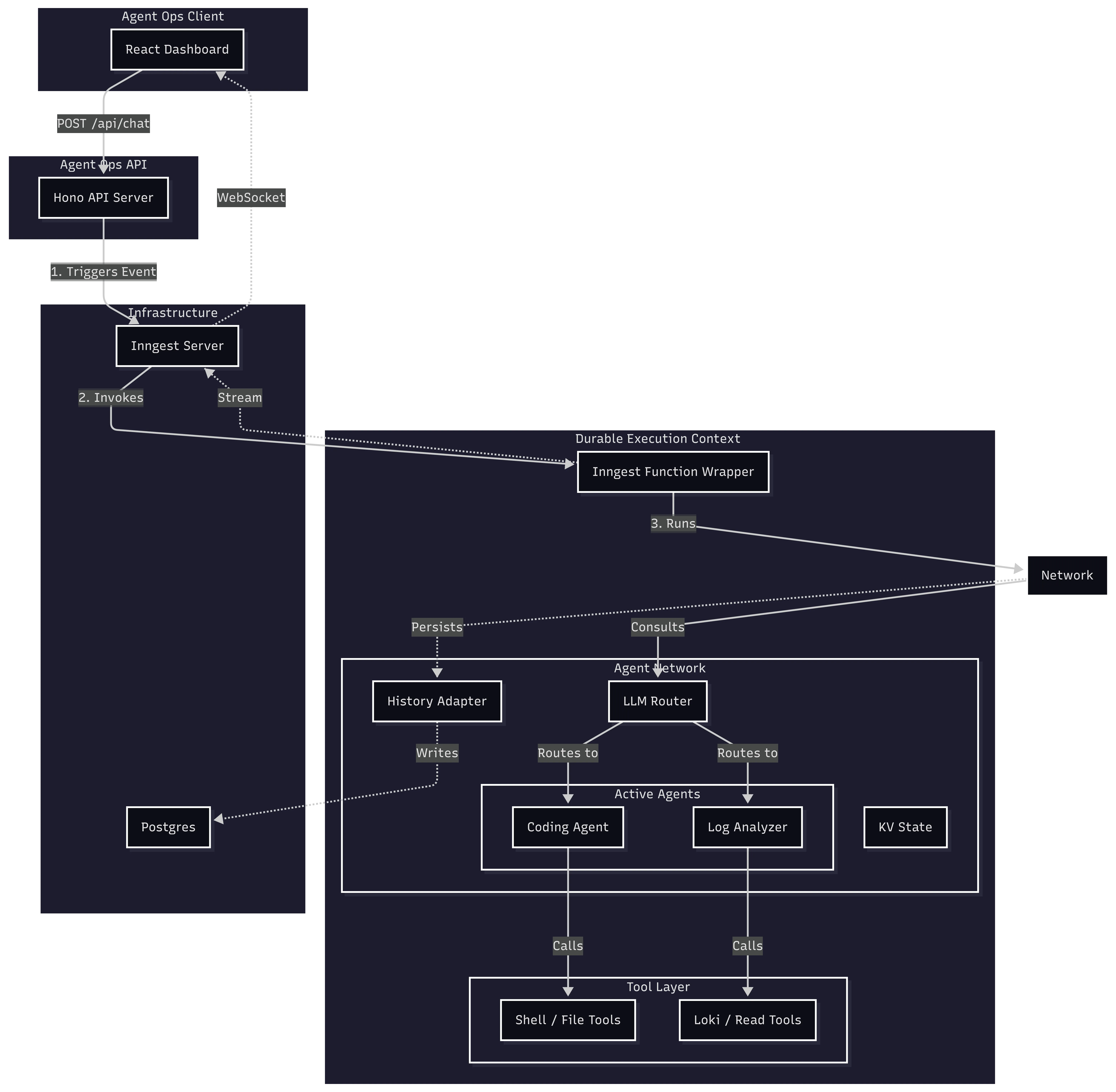

In this new version, I broke the architecture down into four distinct layers: a React client for the UI, a Hono API for orchestration, the Inngest AgentKit for the durable logic, and the Infrastructure (Postgres and the Inngest Server) that keeps it all running.

Here is how these pieces fit together:

1. The Trigger: Hono API

It all starts with a standard web request. I stick with Hono as my API server because it’s lightweight and fast. It handles the initial chat request, authentication, and token generation.

Crucially, when the dashboard sends a message to /api/chat, Hono doesn’t actually run the agent. That would be fragile. Instead, it pushes an event to Inngest and immediately responds with the thread ID. This keeps the API snappy and resilient—the user gets an immediate ack, and the heavy lifting happens in the background.

// ops/src/server.ts

app.post('/api/chat', async (c) => {

// ... validation ...

// Send event to Inngest for durable execution

await inngest.send({

name: 'agent/chat.requested',

data: { threadId, userMessage, userId },

});

return c.json({ success: true, threadId });

});

2. The Container: Inngest Function

The event triggers the Inngest Function. This is the safety net. It provides the execution context, retries, and durability. If the server restarts mid-thought, this function ensures we resume exactly where we left off without losing a single bit of context.

// ops/src/inngest/functions.ts

export const agentChat = inngest.createFunction(

{ id: 'agent-chat' },

{ event: 'agent/chat.requested' },

async ({ event, step }) => {

// The entry point for every agent interaction

// We instantiate the network here and run it

}

);

3. The Brain: Agent Network

Inside that function, we instantiate the Network. Think of this as the “meeting room” for the agents. It holds the shared state (memory) and manages the conversation history.

State management here is two-fold:

-

Long-term History: Using a historyAdapter, it automatically loads and saves the conversation to Postgres. This ensures that when the agent wakes up, it remembers everything that was said.

-

Ephemeral State (KV): The network.state.kv store allows agents to pass data to each other. For example, the LogAnalyzer finds an error and drops it in the KV store; the CodingAgent then reads that error to know exactly what to fix.

// ops/src/network.ts

export function createAgentNetwork({ publish }: FactoryContext) {

return createNetwork({

name: 'ops-network',

agents: [codingAgent, logAnalyzer],

// Built-in History Management

history: {

createThread: async ({ state }) => { /* ... */ },

get: async ({ threadId }) => {

// Load history from Postgres via our adapter

const messages = await historyAdapter.get(threadId);

return convertToAgentResults(messages);

},

appendUserMessage: async ({ threadId, userMessage }) => { /* ... */ },

appendResults: async ({ threadId, newResults }) => { /* ... */ },

}

});

}

4. The Decision Maker: Router

I use an LLM-based router to orchestrate the agents. Instead of writing a bunch of brittle if/else statements, I let a fast model (claude-3-5-haiku) analyze the conversation state and decide which agent is best suited for the next step.

// LLM-based routing logic

router: async ({ network, input }) => {

// ... logic for completion checks, sticky routing, etc. ...

// Use a fast model to classify intent

const decision = await classifyIntentWithLLM(input);

return decision.agent === 'coding' ? codingAgent : logAnalyzer;

},

5. The Workers: Agents

We define the agents using a factory pattern. This is a nice pattern because it allows us to inject dependencies—specifically, a publish function that I’ll use later for streaming real-time updates and requesting human approval.

Here is my Coding Agent, which specializes in analysis and repairs:

// ops/src/agents/coding.ts

export function createCodingAgent({ publish }: FactoryContext) {

return createAgent({

name: 'coding',

description: 'Code analysis, debugging, and repairs...',

system: ({ network }) => {

// Access shared state from other agents

const logFindings = network?.state.kv.get(STATE_KEYS.LOG_FINDINGS);

return codingSystemPrompt({ logFindings });

},

tools: [

// Safe tools (read-only)

readFileTool,

searchCodeTool,

// Dangerous tools (require HITL, injected with publish function)

createShellExecuteTool({ publish }),

createWriteFileTool({ publish }),

],

});

}

6. The Hands: Tools

Finally, agents need to interact with the world. In AgentKit, tools are simply functions that define a schema and a handler.

If this hierarchy—Functions, Network, Router, Agents, Tools—sounds familiar, it is because these are similar to the building blocks I hacked together in Part 2. The difference is that this time, I didn’t have to write the orchestration engine, the state manager, or the retry logic myself. The framework formalized the patterns I was already using, swapping my fragile “glue code” for vetted, production-ready primitives.

Real-Time Updates: From Homegrown SSE to Managed Streaming

In Part 2, I wired up a custom Server-Sent Events (SSE) endpoint to push updates to the client. It worked, but it meant I was stuck managing connections, handling heartbeats, and tracking client state manually. It was a “push” system, sure, but it was my push system to maintain.

In this version, I ditched the manual plumbing for Inngest’s built-in streaming. I still push updates, but now I just call publish inside my agent loop, and the framework handles the WebSocket delivery.

In my main chat function, I inject a custom publish handler into the agent network:

// ops/src/inngest/functions.ts

export const agentChat = inngest.createFunction(

{ id: 'agent-chat' },

{ event: 'agent/chat.requested' },

async ({ event, publish }) => {

// ... setup

const agentNetwork = createAgentNetwork({

publish: async (chunk) => {

// Push every token, tool call, and status update to the client via WebSocket

await publish({

channel: `user:${userId}`,

topic: AGENT_STREAM_TOPIC,

data: { ...chunk, timestamp: Date.now() },

});

}

});

// Run the network

await agentNetwork.run(userMessage.content, { /* ... */ });

}

);

The frontend subscribes to this channel using a token generated by my server. The result is a snappy, chat-like experience, even though the backend is actually running complex, long-running durable functions.

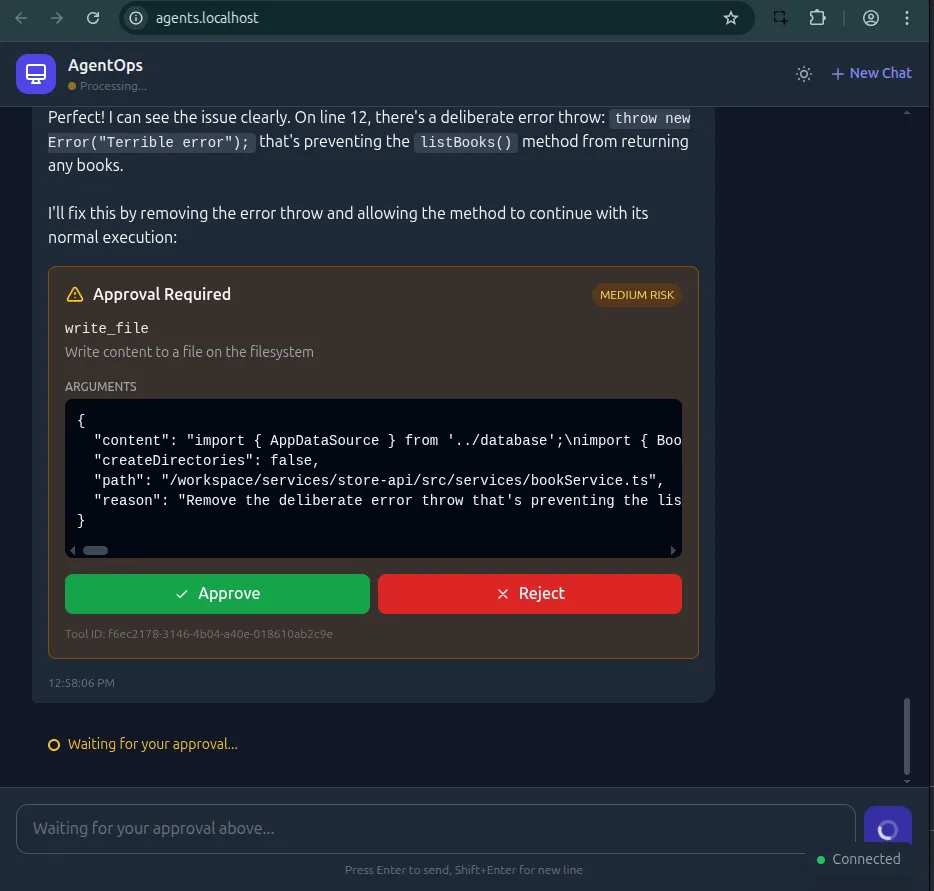

Human-in-the-Loop: The Right Way

Letting an AI execute shell commands is terrifying. One wrong hallucination and you could accidentally wipe a directory. That level of power requires strict guardrails.

I implemented a Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) flow that effectively freezes the agent in time until a human explicitly approves the action.

Inngest handles this elegantly with step.waitForEvent. When the agent hits a dangerous tool, it doesn’t just block a thread. It pauses the function, dehydrates the state to the database, and stops running. It costs nothing while waiting—no idle servers burning money while I sleep.

Here is the implementation of my shell_command_execute tool:

// ops/src/tools/shell-tools.ts

export function createShellExecuteTool({ publish }: FactoryContext) {

return createTool({

name: 'shell_command_execute',

handler: async ({ command }, { step }) => {

// 1. Generate a unique ID for this specific tool call

const toolCallId = await step.run('gen-id', () => crypto.randomUUID());

// 2. Notify the user (via dashboard) that approval is needed

await step.run('request-approval', async () => {

await publish(createHitlRequestedEvent({

requestId: toolCallId,

toolInput: { command }

}));

});

// 3. Pause and wait for the 'tool.approval' event

// This can wait for hours or days!

const approval = await step.waitForEvent('wait-for-approval', {

event: 'agentops/tool.approval',

if: `async.data.toolCallId == "${toolCallId}"`, // Match this specific call

timeout: '4h',

});

if (!approval.data.approved) {

throw new Error('Command rejected by user');

}

// 4. Execute only if approved

return execSync(command);

},

});

}

This pattern is incredibly powerful. It gives me safety without sacrificing the autonomy of the agent logic. The agent proposes a plan, I check it, and then it gets to work.

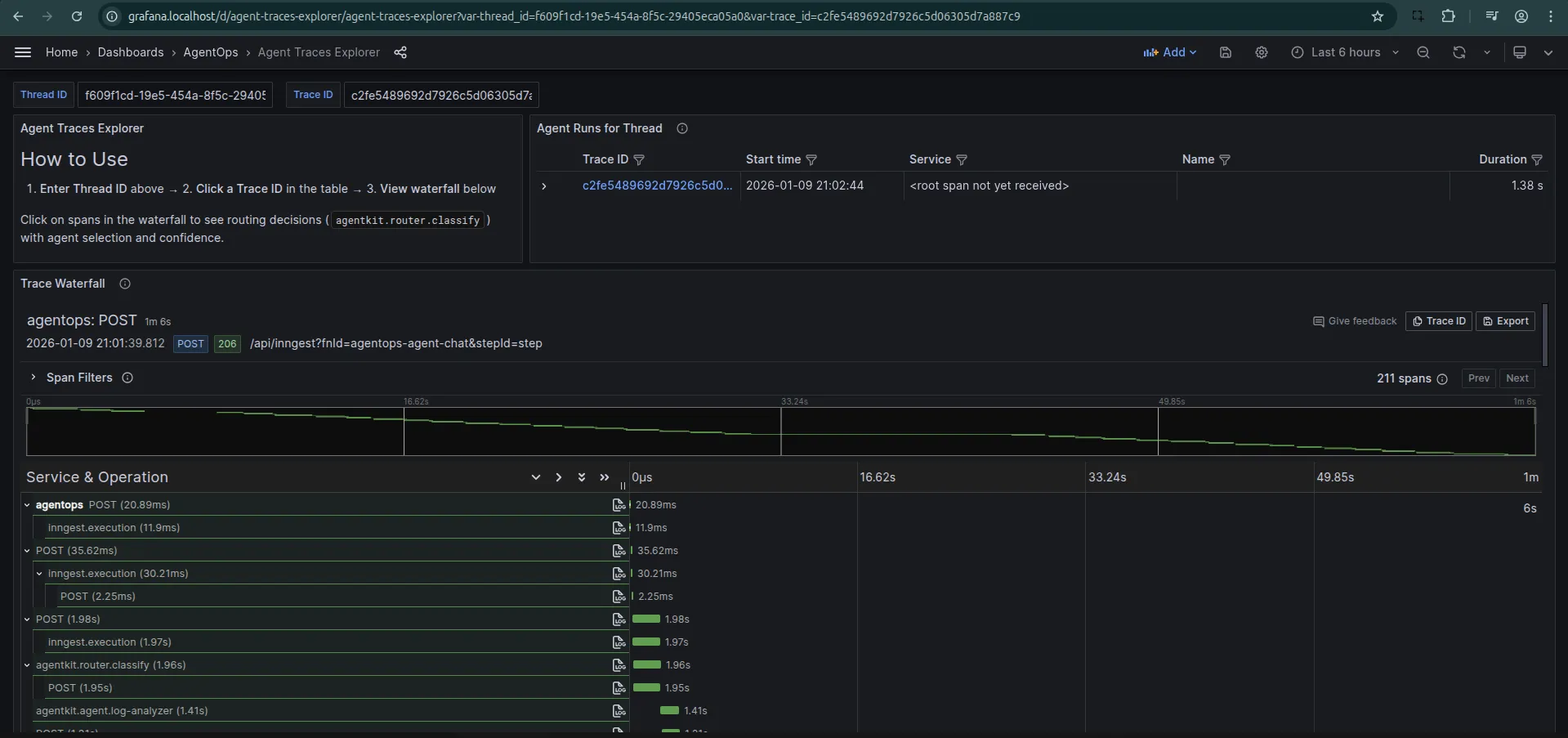

Observability with OpenTelemetry

Finally, there is the issue of visibility. You can’t improve what you can’t measure. I use OpenTelemetry (Otel) to trace every thought, tool call, and routing decision my agent makes.

I configure the NodeSDK to include the InngestSpanProcessor, which links Inngest’s function traces with my application traces.

// ops/src/telemetry.ts

sdk = new NodeSDK({

resource: resourceFromAttributes({

[ATTR_SERVICE_NAME]: 'agentops',

}),

spanProcessors: [

new BatchSpanProcessor(traceExporter), // Export to Tempo

new InngestSpanProcessor(inngest), // Link with Inngest

],

});

This gives me a waterfall view of the entire agent lifecycle. I can see exactly how long the router took, which tools were called, and where latency spikes are occurring.

What’s Next?

I’ve moved from a custom, brittle loop to a robust, scalable framework. I have real-time streaming, secure human-in-the-loop execution, and deep observability.

But is the agent actually good at its job?

Honestly? Not really. Not yet.

It still hallucinates. It sometimes gets stuck in loops trying to fix the same error over and over. But I see that as a data problem, not a systems problem.

Now that I have a durable chassis (Inngest) and eyes on the inside (OpenTelemetry), I can actually start the work of “tuning the engine.”

In the next part, I’ll focus on Evaluation. I’ll use this foundation to build a testing suite that measures the quality of my agent’s decisions and prevents regression as I iterate on its prompts and tools.