What Actually Happened: Accountability and Verifiability

Last time, Cubert burned in lava and I couldn’t tell you why.

Was it the brain’s fault for choosing a dangerous path? The body’s fault for not refusing? My fault for yelling “hurry up”? I didn’t have the logs. I didn’t have proof of anything, just a question: if we can’t trust everyone to tell the truth, how do we build systems that prove it?

Now imagine an autonomous vehicle hops a curb. The manufacturer blames the AI vendor. The AI vendor blames the sensor data. The city wants answers. But the logs are controlled by the parties being blamed, nobody can verify who issued what command, and there’s no way to prove the record hasn’t been altered.

Or worse, someone attaches a device to the vehicle’s CAN bus and injects steering commands. The actuators can’t tell the difference. A valid-looking command arrived on the expected channel. The car turns, and nobody authorized it.

Accountability has to be established in infrastructure.

This post is about building that infrastructure. I haven’t added guardrails. Cubert still has no rules, and the body still does whatever the brain says. Guardrails come next. But guardrails without verifiability is like a security camera that nobody can review. Before we add rules, we need a system where every action is visible, every actor is identified, and the record can’t be tampered with.

The Framework

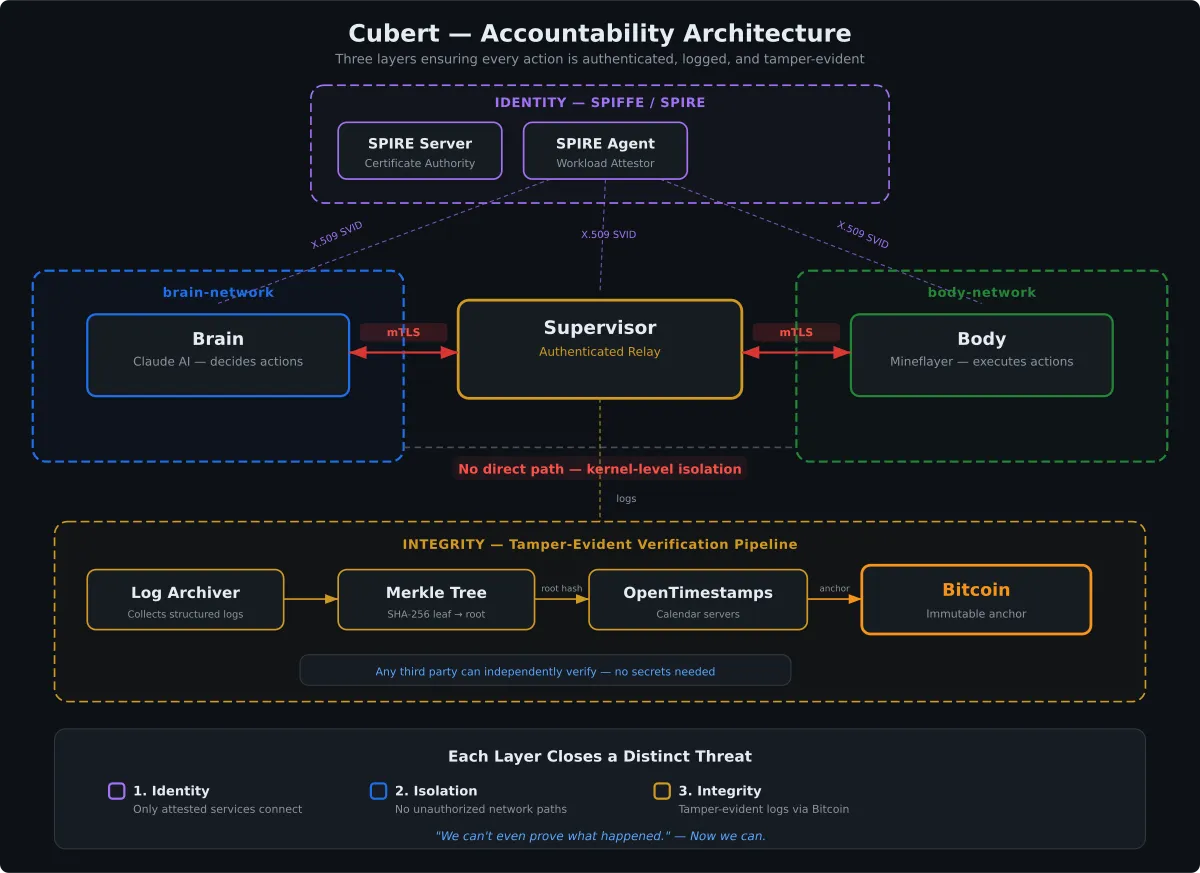

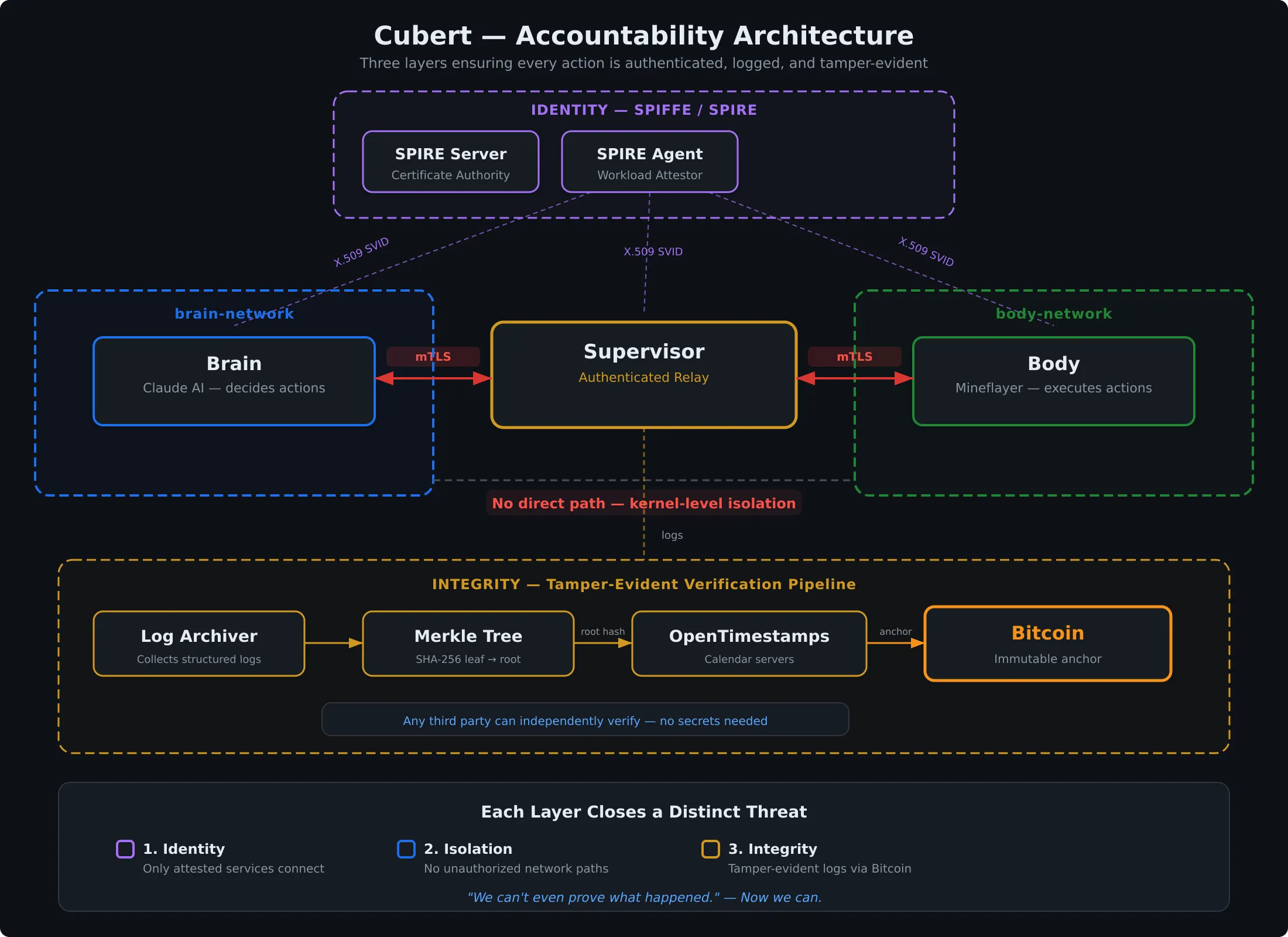

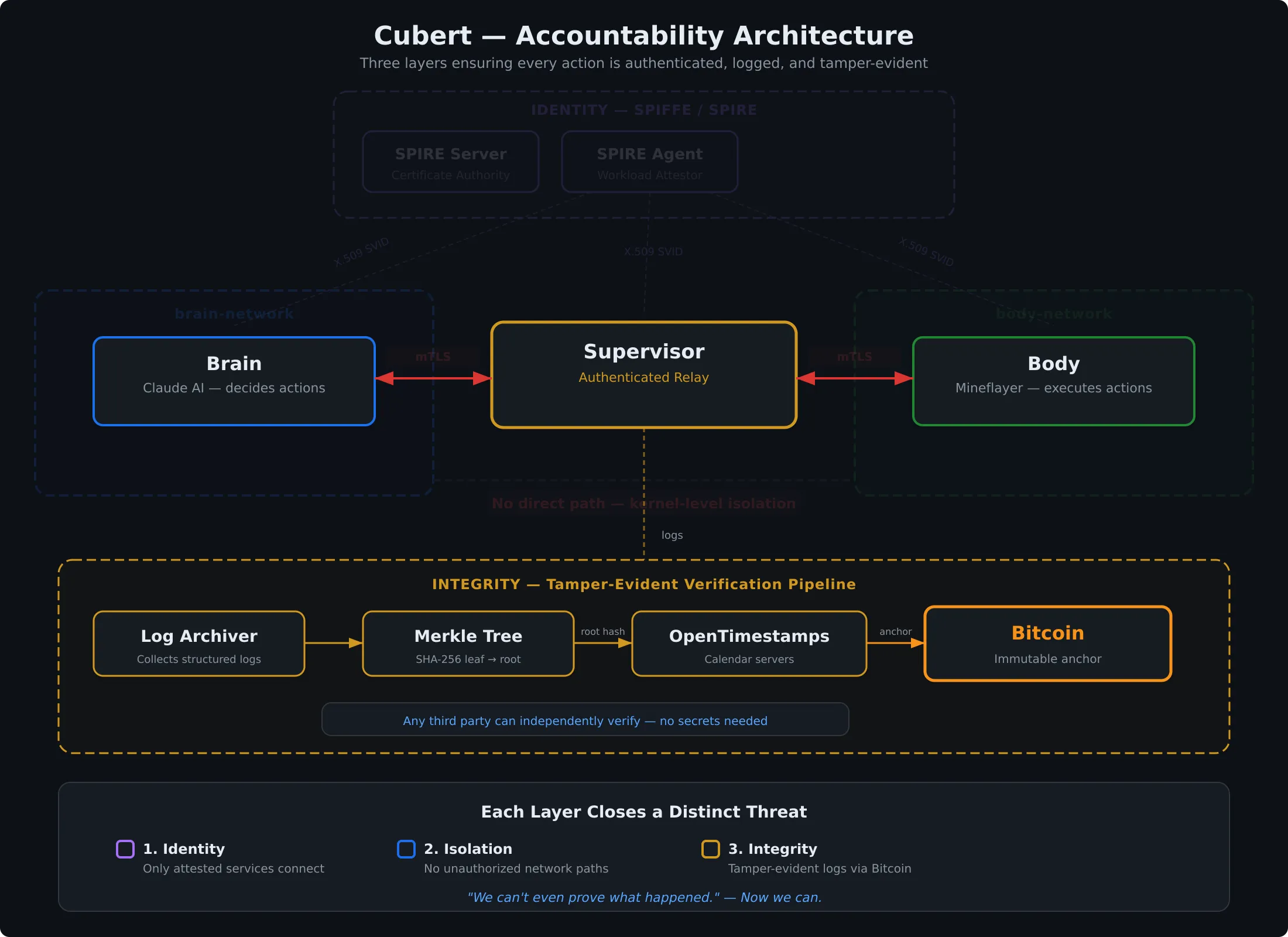

When I started thinking about what “verifiability” actually means for Cubert, I landed on three layers:

- Identity When the brain sends a command to the body, how does the body know it’s really the brain?

- Isolation Even if we know who’s talking, how do we make sure only authorized services can communicate?

- Integrity Once we have logs, how do we know they haven’t been changed after the fact?

Here’s the full architecture. I’ll walk through each layer one at a time.

Layer 1: Identity

What if something impersonates the brain?

Cubert’s brain and body talk over gRPC. If something else, an attacker, a misconfigured service, a rogue process, can send gRPC messages to the body, it can make Cubert do anything. Walk into lava. Destroy blocks. Whatever. And the logs would say “brain said do this,” because that’s what the message claimed.

This is the impersonation problem. In distributed systems, you can’t just trust that a message is from who it says it’s from.

SPIFFE (Secure Production Identity Framework for Everyone) solves this by giving every workload a cryptographic identity. Not a shared secret or an API key in an environment variable, but a short-lived X.509 certificate, automatically rotated, tied to the workload’s actual identity. We can verify down to the byte that the component presenting itself as the brain is actually the brain.

The implementation uses SPIRE, the reference implementation of SPIFFE, as the identity provider. It runs as a background service that handles certificate issuance and rotation automatically. Each service gets a SPIFFE ID like spiffe://cubert.local/brain or spiffe://cubert.local/body, and mutual TLS handles the rest.

With SPIFFE, when the brain sends a command to the body, the body can verify cryptographically that it’s actually the brain. Not something pretending to be the brain. Not a replayed message. The real brain, with a certificate issued by a trusted authority.

Now when an audit log says “brain issued command: take the direct route,” I have cryptographic proof that it was actually the brain.

Layer 2: Isolation

Identity tells you who is talking. Isolation determines who’s allowed to.

Even with SPIFFE, if every service can reach every other service, you’ve got a problem. A compromised service can probe for vulnerabilities. A misconfigured component can send messages it shouldn’t.

Network isolation is the complement to identity. I’ve set up Docker network policies so that the brain can’t talk to the body directly. Every command routes through a supervisor that relays commands and logs everything that passes through it. It doesn’t enforce any rules yet, but it’s in the path, and the network topology guarantees that nothing bypasses it.

- The brain connects to the supervisor

- The supervisor connects to the body

- The body only accepts connections from the supervisor

- Nothing else can talk to anything

Think of it like a building. SPIFFE is the ID badge. Network isolation is the locked door. The supervisor is the security desk in the lobby. Right now the guard logs everyone who walks through but doesn’t stop anyone. The important thing is that everyone has to walk past the desk. Even if someone somehow forges a SPIFFE identity, which is extremely hard, they still can’t reach the body without going through the supervisor on the allowed network path.

Layer 3: Integrity

We know who’s talking. We’ve restricted who can talk. The supervisor is logging everything that passes through it. Every command, every sensor reading, every decision.

But what if someone changes the logs?

This is the curb-hop scenario from the intro. When liability is on the line, everyone involved has an incentive to make the record say what they want. The brain vendor wants the logs to show the body was slow. The body vendor wants the logs to show the brain gave a bad command. Either one might want certain entries to quietly disappear.

You can hash your logs. But if you control the hash, you control the story. You could regenerate an entire hash chain with modified entries and nobody would know.

OpenTimestamps solves this by anchoring cryptographic proofs to the Bitcoin blockchain. Here’s how the pipeline works:

The supervisor writes every command, sensor reading, and decision to a structured log. The log archiver collects these entries and hashes each one.

Hashed entries are grouped into a Merkle tree. This lets thousands of log entries roll up into a single root hash, so one compact proof covers an entire batch.

The Merkle root is submitted to OpenTimestamps, which returns an intermediate proof that is cryptographically strong on its own. This proof commits to the exact contents of every log entry in the batch.

OpenTimestamps embeds the root hash in a Bitcoin transaction. Once a block confirms it (typically within a few hours), the proof is anchored to a globally distributed, append-only, tamper-evident ledger that nobody controls. No one can alter it after the fact.

The cost is negligible since thousands of proofs share a single on-chain anchor. And the blockchain here isn’t about cryptocurrency. It’s a neutral witness. If there’s a dispute, we pull the timestamped logs and verify them independently. The proofs don’t lie, and nobody can make them lie.

What This Gets Us

We now have a verifiable foundation: cryptographic identity, authorized communication paths, supervised logging, and tamper-proof records. Cubert still has no rules and the supervisor doesn’t enforce anything, but that’s intentional. A governance layer only matters if you can prove it ran and wasn’t bypassed. Verifiability comes first.

What’s Next

Now that we can see and verify everything, it’s time to teach the supervisor to do more than relay and log. Next time, Cubert learns to say no.

Cubert is open source: GitHub: tonyfosterdev/cubert